Merrie Monarch Festival, Hilo, Hawaii Island

8 Places to Find Your Inner Hawaiian

Why bother going to Hawaii, anyway? It’s a long way away—the most isolated islands on Earth. Other places have pristine beaches and abundant sunshine. Groups can go elsewhere for fresh seafood and umbrella drinks; and for tropical backdrops, whale watching and colorful history.

But Hawaii has its special sauce. At a time when meeting planners are more attuned than ever to authentic destinations and immersive, experiential programs, only the Aloha State offers up… Native Hawaiian culture.

But what it that, exactly? You may think you know, but it’s more than a flower lei placed around your neck in welcome. More than a blousy shirt ablaze with exotic blooms or surfing memes. More, even, than a festive luau—though at the best of these, you’re getting warmer. Like all genuine cultural expressions, Native Hawaiian culture is not a tourist performance. It is lived, venerated and passed from generation to generation.

Visitors to Hawaii quickly sense this from almost the moment they arrive. Hotels showcase Hawaiian crafts and culture, and many offer cultural visits by a Native Hawaiian to “talk story.” Everywhere you go on these islands, you will see and hear words of the Hawaiian language. This renaissance of Hawaiian culture—language, dance, arts, customs—began in the 1970s, says Native Hawaiian lifestyle and cultural writer Stephanie Launiu. It’s a shift shadowed by a long and often bitter colonial history during which native customs and culture were diminished and even banned.

Let us look, then, to where this revival is most evident—Maui and the Island of Hawaii, where Native Hawaiians are most populous. As of 2014, some 364,000 residents out of a statewide population of 1.4 million, or about 26 percent, identified as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander. But Hawaii Island’s indigenous population stood at 34.4 percent; next was Maui, at 27.7 percent (including Molokai and Lanai, both in Maui County).

On Hawaii Island and Maui, then, here are the best places to learn what being Hawaiian really means.

Hawaii Island

Hula to the Max at Merrie Monarch Festival

Held in Hilo on the island’s windward coast, this weeklong celebration of all things hula begins each year on Easter Sunday. It’s the Super Bowl of hula, drawing participants who practice year-round from halau (hula schools) from every island, the mainland and beyond. But it’s more than that—dating to 1963, it’s credited with spurring an upsurge in Native Hawaiians’ pride in their history and culture.

The festival is named in honor of King David Kalakaua, last monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii, who reigned from 1874 until his death in 1891, and was known for his fun-loving ways. He is credited with reviving and nurturing Native Hawaiian culture and practices, including its mythology, medicine and hula, the islanders’ form of storytelling through dance. Missionary teachings had suppressed many of these traditions for generations. A royal court is chosen to represent the king and his family to exemplify maturity, humility and pride in the Hawaiian culture.

The first four days of the festival offer free, noncompetitive events such as performances by halau from as far away as Japan, and a native arts and crafts fair. Other highlights include a grand Merrie Monarch Parade, the crowning of Miss Aloha Hula— winner of the competition among individual female dancers in both modern and traditional forms of the dance and chant—and group hula competitions.

Proceeds from the festival support educational gatherings and scholarships.

Sighting Hawaii Past

|

|

|

| Top: Hulihee Palace, Kailua-Kona; right: Puuhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park, Kohala Coast | ||

Set your group’s sights on a trio of Hawaii Island historical sites. Puuhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park, south of Captain Cook on the western (leeward) coast, is a 420-acre living museum on the site where, as recently as the early 1800s, Hawaiians who broke a kapu (an ancient law, or taboo) could avoid being put to death. Puuhonua means “place of refuge.” A priest could absolve the offender, and then he was free to leave. Defeated warriors could also find safety there.

Just outside the wall that encloses the refuge, exalted chiefs had their homes. The park complex includes archeological sites of temple platforms, royal fishponds and remains of coastal villages. There’s also the reconstructed Hale o Keawe heiau, a temple built by a chief from Kona to entomb the bones of his father. Other nobles were buried there, too, and it was believed this sacred area got its mana (power) from these regal remains.

Cultural demonstrators in the park often play ancient Hawaiian games, weave baskets from coconut fronds and make bracelets from laulau (leaves from the pandanus tree).

Just north, on the Kohala Coast, Puukohola Heiau National Historic Site is the oldest heiau in Hawaii. It was erected by Kamehameha the Great, a conqueror of rival rulers whose closest European counterpart might be Napoleon. Kamehameha spent much of his time near Puuhonua o Honaunau, but, frustrated in his attempts to unite all the Hawaiian islands, built this temple on the advice of a seer. Ultimately, he prevailed in his mission, having “accomplished what no man in the history of the Hawaiian people had ever done,” as a U.S. National Park Service website asserts. “By uniting the Hawaiian islands into a viable and recognized political entity, Kamehameha secured his people from a quickly changing world.” Guided tours are available for groups of 10 or more for $2 per person.

With a visit next to Hulihee Palace, in historic Kailua-Kona, groups can leapfrog from Hawaii’s first king to its last. The palace was originally built of lava rock and coral lime mortar, and home to the brother of Kamehameha the Great’s favorite wife. Over the generations it was home to more Hawaiian royalty than any other residence in Hawaii. In the 1920s, it almost fell to the wrecking ball in favor of an oceanfront hotel, but today it still stands as a museum showcasing artifacts from the era of King Kalakaua and his wife, Queen Kapiolani, including superb koa-wood furniture, feather work and Hawaiian quilts.

Tours are self-guided or docent-led. One Sunday a month, the palace hosts Afternoon at Hulihee Palace, with hula and mele (chants, songs or poems) on the property’s lawn starting at 4 p.m.

Talk Story at Lyman Mission House

Lyman Mission House, in Hilo, dates to 1839, making it the oldest wooden structure on the Island of Hawaii, and one of the oldest in the state. Next door, Lyman Museum is a Smithsonian-affiliated natural history museum that houses an important collection of artifacts and tells the story of Hawaii’s islands and people. Exhibits trace Hawaii’s history—from its volcanic origins and the flora and fauna that arrived before humans—to life in ancient Hawaii and since. The Mission House itself, home to New England missionaries David and Sarah Lyman, was a gathering place for many of the Hawaiian alii (royalty), as well as visiting notables such as Mark Twain and Isabella Bird; it’s open by guided tour only, limited to 10 guests at a time.

Travaasa Hana, Maui

Throughout the year, the museum hosts educational programs ranging from lectures to hands-on workshops for Hawaiian skills and crafts.

By visiting both venues, groups can glimpse life as it was 150 years ago, as well as immersive exhibits on many aspects of Hawaiian natural history and culture. “A rare and well-rounded view of the real Hawaii,” the museum’s website promises.

Maui

Explore the Heart of Maui Culture

Not only is Maui Arts & Cultural Center (MACC) a world-class performing arts venue and visual-art powerhouse; its programs showcase authentic Hawaiian artistic experiences that spring from rich cultural traditions. Indeed, half of its offerings celebrate regional and local culture, and a core tenet of MACC is that Hawaiian culture is vital to the identity of the institution.

For instance, Wearable Art Show in early June focuses on Hawaiian cultural motifs and practices such as kapa (a fabric made form the fibers of trees and shrubs), lauhala (leaves of the hala tree) weaving, weaponry, tattoo and personal adornment. Maui Ukulele Festival, a free event staged in mid-October, pays tribute to the most recognizable of traditional Hawaiian music. Next month’s performances will include Maui-born Kealii Reichel, whose passion for the language and culture of Hawaii led him to become the founding director for Punana Leo o Maui (Hawaiian language immersion school) and to establish his own halau (hula school; literally “a branch from which many leaves grow”).

The facility is on par with what you might expect in a medium-sized city, yet it’s in Kahului, population 26,300. Its meetings, performances and events attract 25 million visitors annually. Two indoor theaters seat 1,200 and 5,000, respectively. An outdoor amphitheater features a 4,096-square-foot shaded pavilion. To one side of the amphitheater, a simple mound of earth with river rock is Maui’s first recorded pa hula, a space dedicated to the ancient tradition of hula.

Hang Loose in Heavenly Hana

You can’t get much more “real Hawaii” than Hana Town, on the island’s isolated northeast coast, where most of the 1,200 or so residents are Native Hawaiian. It’s a beautiful, almost surreal place—a step back in time and attitude. Getting there is more than half the fun on the 68-mile Road to Hana, a rain-forest drive of more than 50 one-lane bridges, 600 curves, waterfalls, tropical streams and pools, bamboo jungles, spectacular cliffs and exotic flora petals strewn across the narrow ribbon of asphalt. Fortunately, groups have other people to do the driving, and the eco-friendly tour company Valley Isle Excursions is an old pro at this.

Did You Know?

Ukulele means “jumping flea” and dates to the 19th century.

The ultimate Hana visit includes an overnight at 70-room Travaasa Hana, which recently completed a $12 million refresh with largely sustainable materials. The kitchen is stocked by local organic farmers and fishermen. Most of those who work at the luxury hotel have deep Hawaiian roots, and cultural performances and demonstrations such as throw-net fishing and lei making come from the heart. Among the must-do activities is the short trip to crescent-shaped Hamoa Beach, extolled by author James Michener as the most beautiful in the Pacific. Meeting space totals more than 5,000 sq. ft. Hotel buyouts are welcomed.

Enjoy Some Slack

Most of us think ukulele when Hawaiian music comes up. The word translates roughly to “jumping flea.” The ukulele dates to the 19th century, and was an adaptation of the Portuguese machete, another small, guitar-like instrument. But at roughly the same time, Mexican and Spanish vaqueros (cowboys), hired to teach Hawaiians how to handle cattle on the Big Island, were strum

strumming their guitars around their campfires. Hawaiian paniolos (also cowboys) adapted the vaquero technique to invent ki hoalu (slack key guitar), one of the world’s great acoustic guitar traditions. Ki hoalu literally means “loosen the key,” and accordingly, the strings are slacked to produce unique and beautiful tunings.

MACC hosts a yearly, free Ki Hoalu Guitar Festival in June. Slack key stylists also perform at venues around the island throughout the year, but the slack standout is the weekly Slack Key Show-Masters of Hawaiian Music at Napili Kai Beach Resort. This concert series is hosted by George Kahumoku Jr., a four-time Grammy Award-winner and taro grower.

Book It, Dan-O

Maui has many tour companies eager to lead groups to the most popular sights and adventures. Two outfits, in particular, specialize in immersive Hawaiian culture. Open Eye Tours & Photos offers one-of-a-kind, customized tours of sights not found in guide books or seen from typical tour buses. Cultural tours can include a visit to ancient battle grounds, sacred sites, petroglyphs, monuments and traditional artists’ studios.

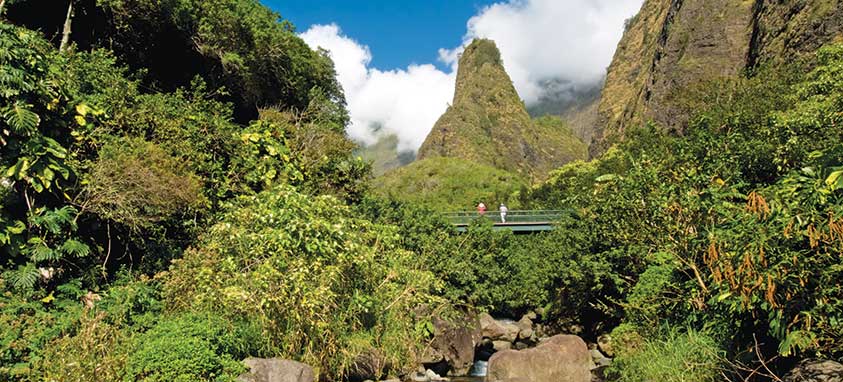

Iao Valley State Park, Maui

Examples of custom tours include a group of doctors who visited a traditional healing sanctuary, to see stones used to pound medicine and learn about plants still grown for their medicinal value; engineers and architects who wanted to see traditional Hawaiian archeological sites and thatched houses; and botanists who were interested in loi kalo (taro patches), sugar cane, pineapples, orchids and native plants in the wild.

Maui Nei Native Expeditions connects history and Hawaiian culture in guided walking tours and arts immersion programs led by Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners who weave their own family stories with historical facts and traditional skills. Among cultural treasures that can be visited are Pohaku Hauola (Hauola Stone), used as a birthing site for the highest-ranking and most sacred alii moi (high chiefs); the King’s Taro Patch, a large taro farm cultivated by Kamehameha the Great and his sons to demonstrate the dignity of labor; Mokuula Island, the royal residence of Maui’s high chiefs since the 16th century and where Kamehameha III ruled the Kingdom of Hawaii until 1845; and Hale Halawai, a re-creation of a thatched meeting house in a beachfront park where Hawaiian royalty used to feast and relax when present-day Lahaina was called Maluulu o Lele (the breadfruit grove of Lele).

A cultural experience with Open Eye Tours & Photos

Where History was Changed

Towering emerald peaks guard the lush valley floor of Iao Valley State Park. Located in Central Maui just west of Wailuku, this 4,000-acre, 10-mile-long park is home to one of Maui’s most recognizable landmarks, the 1,200-foot-high Iao Needle. This iconic, green-mantled rock outcropping overlooks Iao stream.

The scene is eminently peaceful now, but the stream was once so littered with fallen bodies that it ceased to flow. It was here in 1790 that Kamehameha the Great defeated Maui’s army in his quest to unite the islands. The three-day battle was one of the most bitter in Hawaiian history, and ultimately changed its course. An easy, paved walking trail provides a scenic viewpoint of Iao Needle and spectacular views of the valley. A short loop trail meanders through an ethnobotanical garden next to Iao stream.

Luau Love

In ancient Hawaii, a feast to celebrate special occasions was called an ahaaina. Aha means gathering and aina means meal. Celebrating special occasions together was an important cultural tradition. But women were not allowed to eat with men, nor were they allowed to eat certain foods. King Kamehameha II first invited women to join the feast, in 1819.

In ancient Hawaii, a feast to celebrate special occasions was called an ahaaina. Aha means gathering and aina means meal. Celebrating special occasions together was an important cultural tradition. But women were not allowed to eat with men, nor were they allowed to eat certain foods. King Kamehameha II first invited women to join the feast, in 1819.

Over time, luau—which refers to the taro leaf, commonly used in Hawaiian cuisine—became the name for these special parties. It should always involve kalua pig, prepared in an imu (underground oven), poi (pounded taro root), laulau (meat wrapped in taro leaves and steamed in the imu) and poke (raw fish salad made with kukui nut, seaweed, soy sauce and condiments).

Over time, luau—which refers to the taro leaf, commonly used in Hawaiian cuisine—became the name for these special parties. It should always involve kalua pig, prepared in an imu (underground oven), poi (pounded taro root), laulau (meat wrapped in taro leaves and steamed in the imu) and poke (raw fish salad made with kukui nut, seaweed, soy sauce and condiments).

Today’s commercial Hawaiian luau usually features traditional drumming, hula and something really flashy, such as Tahitian fire dancers. It can come off as authentic, or something from a cheesy Hollywood sound stage. Same with the drinks and food—fresh and evocative, or overly sugary mai tais and a tired buffet.

Here are a few of the very best.

Here are a few of the very best.

Island of Hawaii

Mauna Kea Beach Hotel (pictured right) hosts the oldest luau show on Hawaii Island, and one of the island’s most stylish. Its location on the grounds of this iconic hotel in South Kohala adds midcentury modern architecture and golden sunsets. “It’s also smaller than most, which can feel more like an evening with friends and family, and not your local tiki-themed, all-you-can-eat buffet,” says Hawaii Magazine, whose readers rates it No. 1 on the island.

Haleo, the luau at Sheraton Kona Resort & Spa at Keauhou Bay, celebrates the history and people of Keauhou, from the birth of King Kamehameha III to the Battle of Kuamoo, a clash over the traditional kapu religious system. Live performances combine Hawaiian music, dance and culture.

Maui

The Feast at Lele in Lahaina turns the luau into a gourmet repast with a sit-down dinner at individual tables, enthuses travel guide Gayot. “The food is a multicourse culinary tour of Polynesia, including dishes like slow-roasted kalua pork and pohole fern shoots from Hawaii or grilled mango ginger chicken with Tahitian vanilla aioli and mango relish representing Tahiti.” The show climaxes with a vivid Samoan fire-knife dance.

Old Lahaina Luau (pictured right), on Insta-worthy historic grounds in Lahaina, offers high-quality stage performances, service and food. Hula and other dance spans generations, ranging from stories taken from Hawaiian mythology to modern hula. Many of the fruits and vegetables, including the taro for the poi, are grown on the luau’s own farm.

From the Sands of Time

- Polynesians, probably from the Marquesas, arrived on Hawaii Island as early as 400 C.E. They brought “canoe plants”— taro, bananas, breadfruit, coconut and others—as well as pigs, dogs and chickens. Their living structures were arranged in clusters, because men and women had separate eating and sleeping quarters.

- The first recorded western contact with Hawaii came in 1778, when Capt. James Cook (pictured left) discovered Kauai. The next year he sailed into Kealakekua Bay on Hawaii Island. It’s estimated between 400,000 and 1 million Native Hawaiians inhabited the major islands at that time. A century later, European diseases had reduced the Native Hawaiian population tenfold.

- The Kingdom of Hawaii, an internationally recognized monarchy, existed from 1795 to 1893; it had bilateral trade treaties with 17 nations, including France, Italy, Spain, Russia and Japan. In 1893, U.S. and European businessmen and sugar planters got the U.S. government to depose Queen Liliuokalani and seize the kingdom. An investigation ordered by President Grover Cleveland concluded the takeover had been illegal. Nonetheless, Hawaii was annexed as a U.S. territory in 1898, without compensation to anyone. A systematic oppression of Native Hawaiian language and culture began. It was not until 1978 that it again became legal to teach Hawaiian in schools.