2018 Special Olympics torchbearer Beth Knox’s winning meeting tips

If managing a high-profile event that traditionally takes four years to plan in just over half that time with a $15 million budget and a reliance on 15,000 volunteers sounds like a job for a superplanner, then meet Beth Knox. As 2018 Special Olympics USA president and CEO, she went from hiring a leadership team and creating a strategic plan to hosting 4,000 athletes with intellectual disabilities for a jubilant celebration of human spirit—all in just 2 1/2 years.

This was not Knox’s first marathon feat of planning. During her decade-long tenure as president and CEO of Seafair—an annual 10-week-long event featuring aerial and aquatic competitions for some 2 million attendees—she learned the intricacies of managing volunteers, budgets and calendars. “The long lead time changes the rhythm and spreads out the timeline,” Knox says. “The same concepts apply for Special Olympics, but planning takes on a whole new meaning in this context.”

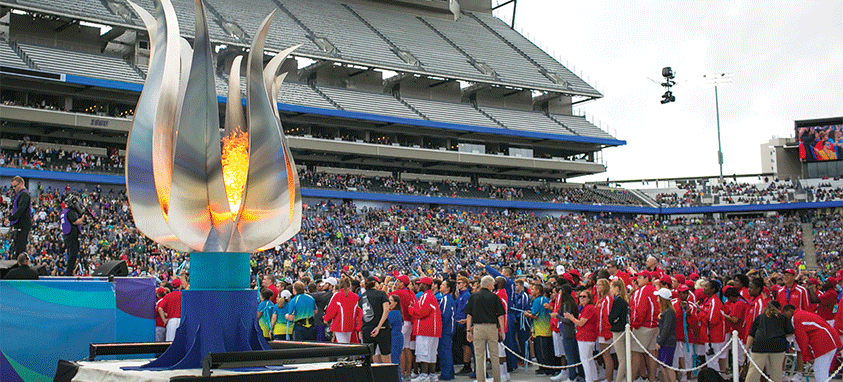

In addition to 16 Olympic-style, individual and team sports—basketball, bowling, gymnastics, powerlifting and stand-up paddleboarding, among others—her team staged heartfelt opening and closing ceremonies and a fireworks finale to end it all.

Early on, Knox made the decision to utilize University of Washington facilities, residences and dining halls. That way, all athletes and their families could be housed in one place to reduce the need for expensive transportation logistics. Husky Stadium on campus was home to most of the competitions; swimming events were staged at Weyerhaueuser King County Aquatic Center—a competition-forced facility built for the 1990 Goodwill Games. She fielded teams of volunteers to escort attendees to their respective fields of competition.

“We called it the walking games,” she said.

Knox felt a sense of urgency from the beginning, and set about instilling that same deadline focus with her partners—Microsoft was the major sponsor—and vendors. “It requires a lot of communication,” she said. That was one of many understatements she uttered during our chat in the days following the closing ceremonies in July.

Here are her training tips learned from the heavy lifting of upholding an inspirational tradition that goes back 50 years to when Eunice Kennedy Shriver orchestrated the first competitive extravaganza in 1968.

Start with a Vision

The intimidation factor can be high when the official description for an annual event reads: “A global movement that unleashes the human spirit through the transformative power and joy of sports, every day, around the world, empowering people with intellectual disabilities to become accepted and valued members of their communities, which leads to a more respectful and inclusive society for all…using sports as the catalyst and programming around health education…to fight inactivity, injustice and intolerance.”

The 2018 Special Olympics team focused on a vision of producing a world-class event that showcased Special Olympics while giving an incredible experience for athletes. Knox’s mission was to deliver exceptional games within budget. “That was pretty straightforward,” she says.

Another main objective was to increase awareness not only of Special Olympics, but also the need for inclusion of individuals with intellectual disabilities. By the time the athletes in their colorful track suits paraded into Husky Stadium to light the torch in the Special Olympics Cauldron, set out to make them familiar faces in the community. A unified sports fundraiser pitted law enforcement, firefighters and celebrity sports stars teamed with Special Olympic Washington athletes against each other. Welcome Days and a Major League Soccer rivalry game between the Seattle Sounders FC and Portland Timbers gave a special shout-out to Special Olympics athletes in attendance. Volunteer health professionals even provided free health screenings and educational sessions.

Stage a Dry Run

To test the logistics in a live setting, Knox scheduled the 2017 North America Golf Championships for 200 athletes one year ahead of the major games, using some of same logistics that would be adapted for the comprehensive games. She started by stationing volunteers at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) to help ferry athletes, coaches and families to housing at University of Washington via light rail. The crowd was a fraction of the size that would show up for the main event, but it forced transportation and housing partners to develop systems that would work for this population. “We could make mistakes and learn from them on a smaller scale,” she says.

Enlist Help Strategically

In addition to a long-term staff of 40 and some 50 volunteers, 15,000 people came out to help during the week of the event. Knox had plans from previous games in Mercer County, New Jersey, and Lincoln, Nebraska, and anticipated the positions she would need to fill. But the call for 10,000 additional hands provoked so much interest that they ended up with half more than that.

The challenge was accommodating all of them and their specific requests. Many corporate partners wanted employees to volunteer together, and some people wanted to work on specific sports or changed their plans as the date drew closer. “We had very low attrition, which is very unusual,” she says. However, if Knox were to do it all over again, she would recruit only six months out and give herself more flexibility in assigning roles.

Leave a Legacy

The last line in Knox’s marching orders was one of the most gratifying. The charge: activate community engagement and leave a legacy of inclusion. “This is a one-time event, but we didn’t want to be one-and-done,” she says. “We wanted to leave a dedication to inclusion in the hearts and minds of the community.”

Sponsors, volunteers and spectators were encouraged to continue to support nonprofits in the region that help people with all types of disabilities. That could mean creating employment opportunities or increasing accessibility for those with disabilities. In fact, a Future of Inclusion Forum held at Seattle Repertory Theater during the event showcased model policies and examples for how life-changing an inclusive mindset can be for all parties involved.

“The concept of a city of inclusion was woven into everything we did,” Knox says, pride in her voice. “My biggest reward was hearing from people how much the event impacted them, and how they saw the world of inclusion with completely new eyes. That meant a lot.”

The other legacy was financial. The games had an estimated economic impact of $76 million. Tom Norwalk, Visit Seattle’s president and CEO, called Knox integral to the community because she “celebrated the diversity that brings us together and creates a stronger Seattle.”

Next

Now that most of the athletes, Knox’s employees and the volunteers have gone back to their lives, she and a core group of four will stay on for another three months completing action reports. Then, she plans to hit the pause button. After a short vacation, she’ll return to continue working to bring people together and build community.