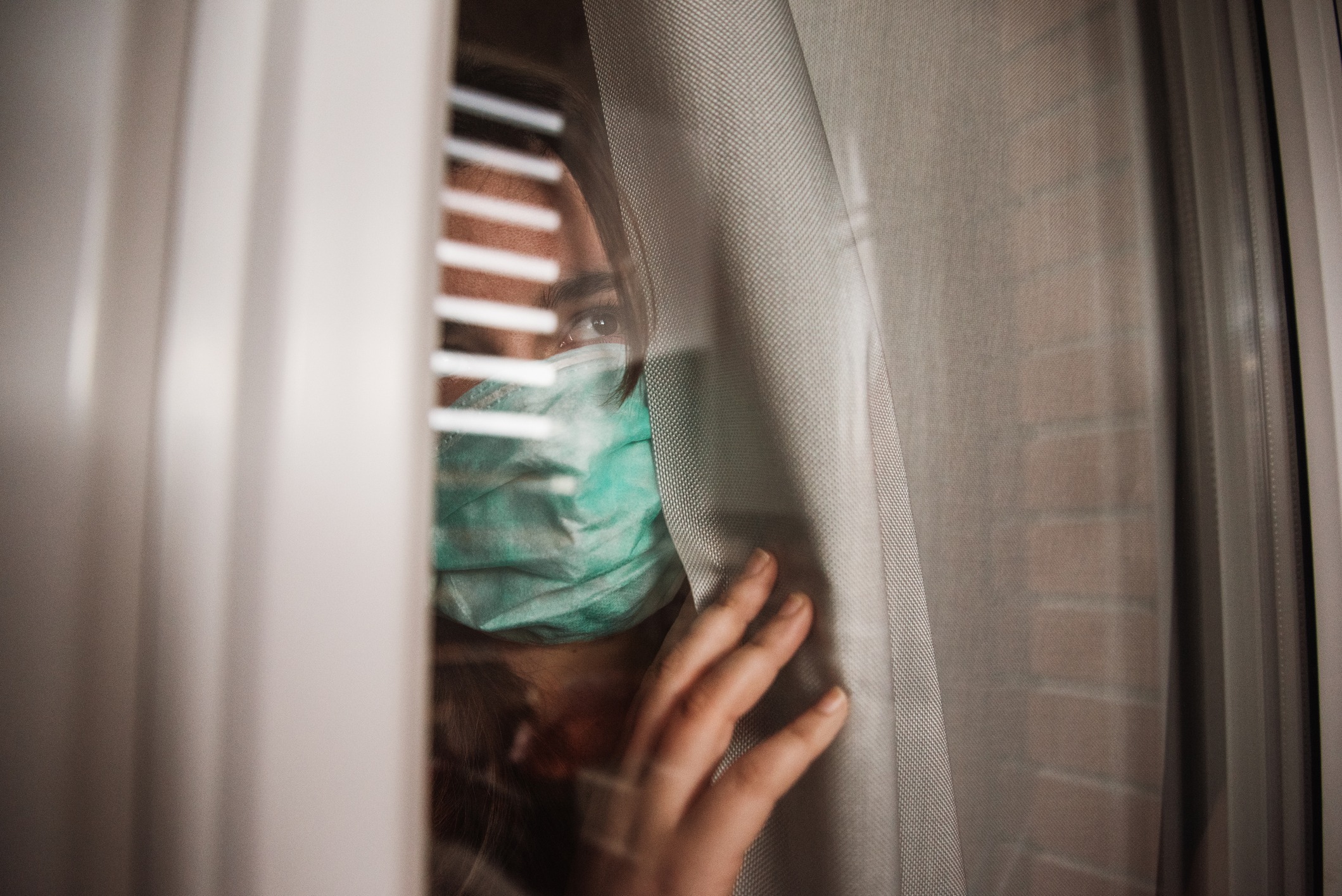

With ongoing concerns related to Covid variants, a number of businesses and events are re-evaluating whether to postpone or cancel despite the relative loosening of federal, state and local restrictions. So, what happens when there aren’t specific government restrictions to trigger a force majeure event to postpone or terminate an event?

Can the more recent trend of “fear” majeure be sufficient grounds to postpone or terminate an event? As any good lawyer will tell you…it depends.

Government Action vs. Fear of Variants

Historically, force majeure events were commonly referred to as an “Act of God” or something beyond your control that prevented or made performance of one’s obligations “impossible, impracticable, or illegal.” When governmental restrictions first started taking effect in response to Covid-19, there were a number of legal questions that arose regarding whether parties could invoke force majeure provisions to postpone or cancel events. Again, it depended on whether the applicable contract contained a force majeure provision and whether that provision was the “long” or “short” form (i.e. laundry list of specific events vs. broad catch-all language).

Read More: Flight Cancellations by the Thousands—Does Your Travel Insurance Cover the Cost?

Folks who did not have force majeure language in their contracts or did not have sufficient provisions and who were able to consult with legal counsel have since revised language to include key terms to invoke that provision in postponing or terminating events (i.e., referencing “disease, viral outbreak, epidemic or pandemic” vs. Covid-19 and/or referencing “governmental actions,” “emergency declaration” or “any law or action taken by a government or public authority”).

Even if you have a force majeure clause or recently beefed it up to reflect the new reality from Covid restrictions, can it be used to invoke postponement or cancellation in the absence of a specific governmental restriction? Maybe and it depends.

Specifically, it depends on whether the basis or reason for the “fear” is sufficient to invoke or fall within the force majeure language. For example, if the “fear” relates to a more generalized concern over, say, the possible rise in infections related to the omicron variant, but there is no specific “governmental action” that mandates closure or cancellation of an event or even if your event is in a location that has mandates against mandates for government shut-downs, what then? The likely answer is that would not be sufficient or meet the threshold of impossibility or impracticability to equate to a force majeure event.

However, if the underlying agreement contained language that specifically addressed the “worried artist” or “fear” issues, then there might be sufficient grounds to invoke postponement or termination. For example, the recent wave of postponed or cancelled shows on Broadway or artists such as Sir Elton John cancelling shows after receiving a positive test were premised on specific language in the underlying agreements that allowed for last minute changes in scheduling. Again, this can be addressed either initially in the contract, or by negotiating additional addendums or riders to the contract after the fact.

On Notice

If attempting to invoke or respond to a “fear” majeure event, one should also pay close attention to and comply with not only any formal notice requirements in the underlying agreements, but also applicable language if there are coinciding event cancellation or business interruption insurance policies.

Read More: How to Write Force Majeure to Protect Your Meeting from the Next Pandemic

So, what happens if you are faced with a “fear” majeure possibility of postponing or cancelling an event? The first thing to do is check the operative agreement and see if there is a force majeure clause and then determine whether the basis for this event falls within that definition (and consulting with a good lawyer, if need be). Next, double-check and confirm whether the notice period was proper and the actual notice was made in compliance with the contract. Then determine where the possible venue of any dispute would be (litigation vs. arbitration), what law would apply, and the potential categories or limits on damages and possible recovery of attorney’s fees. Finally, it all comes down to effective communication and negotiation to determine whether it makes sense to postpone, cancel or enforce the contract and potential litigation.

Ty Sheaks is an attorney, author and faculty legal advisor with International Association of Venue Managers. He will give an update on contractual provisions to keep in mind for negotiations during a special Smart Chat Live! March 22 at 11 a.m. PDT/ 2:00 pm. EDT. Save your seat here.