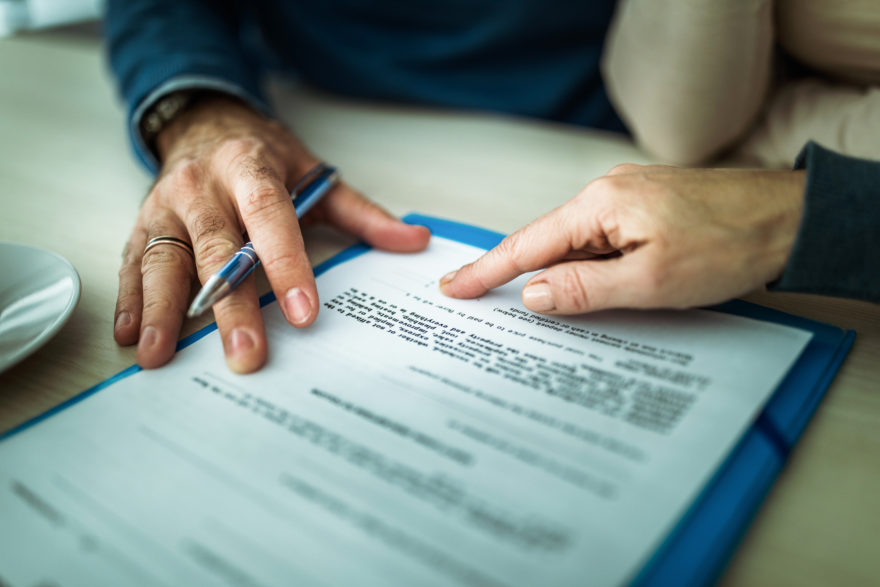

Editor’s note: The lawyer quoted in this article is not providing legal advice. If you are seeking legal advice, consult with a professional.

Addendums, amendments, mutual cancellation clauses, “frustration of purpose”—what do they all mean? And when should each be applied? In the latest Smart Meetings Accelerator “Top Planner Contract Questions Answered,” Lisa Sommer Devlin, an expert in contract law at Devlin Law Firm, answers those very questions (and more) for planners.

If a planner wants to make a change to a contract, is it necessary to sign a whole new contract? Or can some of the wording in the original contract be changed? Is this an addendum?

It’s not an addendum. An addendum is something you add to a contract that is already signed to clarify something.

Let’s say you have a contract to buy 100 bicycles and forget to put what color in the contract. Your addendum would say that 50 bicycles will be blue and 50 will be red. You’re not changing any real terms of the contract; you’re clarifying something that you left out. And it is not something that should be stuck on the back of a contract. You’re supposed to be negotiating one complete document rather than a contract and an addendum.

More: J.D. Devlin: Contracts Made Easy

If you sign the contract and everything’s in place, then COVID comes, and you have to change your meeting spaces, that would be an amendment. You’re changing the contract terms. Everything that wouldn’t change, such as indemnification or insurance, you don’t mention them in your amendment, and they stay in place as is.

Will the onus be on venues and hotels to follow and enforce physical distancing guidelines put in place by the state or province they’re in? Is that up to the planner?

It’s kind of a “nobody knows” answer. If there are requirements under the re-opening, and you can only fill half your tables, yet the restaurant is putting people at every table, the restaurant would be responsible for that. It could get in trouble, depending on what the requirements are.

The problem comes in when you move to a hotel scenario, and you’re having meetings. The hotel is still obligated to follow the requirements, but once people get into the room and they’re moving around, it’s not really clear who’s responsible for going up to two attendees and saying they shouldn’t be sitting so close together.

If you’re the meeting planner in the hotel, are you really going to want to get into an argument with somebody over whether or not it’s appropriate to be sitting too close to someone? Those are unanswered questions at this point, but I don’t think that you want to get into those confrontations. Maybe you can to do things such as have a slide that comes up that says, “Just a reminder: Everybody’s supposed to say six feet apart and wear masks,” and then leave it to people to do what they’re going to do.

How do you advocate for clients when hotels and airlines will not waive cancellation fees?

Let’s look at fundamental fairness. Is it really fair for them to keep this deposit, given all the circumstances? If this event was scheduled in May and the entire state was on a lockdown order, is it really fair for you to keep that that money? It’s got to go back to partnership. We’re in this together, and we need to share the burden. [People who have] submitted their deposits could never have known that this was going to happen.

At the end of the day, there will be circumstances where the party on the other side won’t work with you, and you’re going to have to make a decision about whether to pursue legal avenues. That’s fraught with its own peril.

If hotels will not agree to a mutual cancellation clause, is there a formula to come up with a dollar amount the hotel would have to pay if it can’t fulfill the group?

Mutual cancelation clauses should never be signed and here’s why: If a group cancels a hotel, the damages that the hotel suffers, while they’re difficult to calculate, are easy to understand. They’re out the money from the rooms, from the food, [et cetera].

When a hotel cancels a customer, it’s a completely different equation because it may be that the hotel cancels you a year in advance, and it’s in an urban area and you’re able to book the hotel next door, and the terms are the same, and it doesn’t take much time or effort to book that hotel. So, you really haven’t lost that much.

More: Lisa Sommer Devlin on Advanced Hotel Contract Negotiations

On the other hand, they may cancel you two months out, and you’re in a destination location, and you can’t find another hotel to host your event, and this is your primary revenue source for the year. So, you may be out hundreds of thousands of dollars. It can vary widely.

The point is, the amount of loss that the customer suffers is [unequal] to the loss the hotel suffers. Under the law of liquidated damages, the damages are supposed to be a reasonable estimate of the loss that the injured party would suffer.

Are there any contract clauses for hotels that would give an allowance for future contracts being resigned now that could protect planners if social distancing guidelines continue?

I have seen clauses being put in rebooking agreements that say something to the effect that said event is being rebooked on the assumption that we will be able to have 500 people [in the future]. And if there are restrictions in place that would prevent us from having at least 500 people, then the parties agree that we can terminate this rebooking contract without liability.

See also: How Not to Get Sued If Someone Gets Sick When You Get Back to Planning

Why is a force majeure clause so hard to enforce?

It’s not that it’s difficult to enforce; it’s that you don’t always have enough facts to know [the true situation], and sometimes customers have a subjective belief that they can’t perform when the hotel disagrees. I think that that’s where the disputes come in. I always say that force majeure is like what the Supreme Court said about pornography: It’s difficult to define, but I know it when I see it.

How can planners protect themselves from liability if an attendee gets COVID-19?

I don’t think pre-injury waivers—where you’re signing away your rights to make a claim before something happens to you—are a great idea, and they are extremely difficult to enforce.

It always varies according to state, but having somebody sign a waiver in advance is probably not going to protect you. It’s going to be impossible for anybody to ever prove how they got COVID-19. If I leave my house, get in an Uber, go to the airport, walk through the airport, get on a plane, how am I ever going to prove where I got COVID-19?

The party making the claim would have to show that you that you did something wrong that exposed them to COVID-19. If you’re encouraging them to follow the applicable guidelines in that state, I don’t think they’re ever going to get anywhere [with legal action]. Your protection is having good liability insurance that will defend you. I don’t think a waiver is going to help you, and I don’t think the risk is as big as people may be worried about.

Can you can you specify any force majeure language around riots or in the event of an air transport or hotel strike?

Under the law, strikes are not a force majeure. As long as the hotel has plans in place to go forward with operations, the fact that people may be engaged in labor disputes doesn’t really prevent the meeting from happening. There should be a separate clause [that says] you get notified in the event that there is a strike. At that point, the hotel advises you what they’re going to do to bring in alternate workers or whatever it might be to continue operations.

When planners put generic strikes in their force majeure, they’re opening a whole can of worms. What does that mean? Does that mean a strike by the hotel workers? Does it mean a strike by airline workers? Does it mean a strike by garbage workers? It’s undefined, and it’s just going to cause you problems.

In terms of riots or civil disturbance, most hotels have something in their clauses saying something about these. I usually try to stay within X radius of the hotel.

When those kinds of things happen, if you’re a hotel in the heart of the city where these protests are happening, and the streets are full of people, and you can’t get there, it probably is a force majeure.

When is too soon to start planning again? People are trying to figure out what to do about December. What’s happening now might not be the same as in three months, so how far out can people be planning and contracting right now?

It depends. If your event is for 20 people, that’s a very different thing than if your event is for 2,000 people. And it depends on where this event is going to be scheduled, and it will depend on the nature of your event. I’m not going to give you a hard and fast answer because we don’t know.

If the hotel is open for business, and they can accommodate your people under the applicable restrictions, then it’s probably not a force majeure, and you’re going to have to pay if you don’t have your event.

What if you can have the event but it’s no longer going to be the same as you originally contracted? Maybe only half or 25 percent of the number. What do you do then?

Several years ago, I was speaking at an event in New York, and a Nor’easter [storm] blew in. They probably had less than 50 percent of the expected attendance because people didn’t want to drive in the snowstorm. [The venue] said to the event organizer, “We’re glad you’re coming. We understand that because of the storm you could have tried to work in force majeure, but you didn’t. We’re not going to charge you attrition.”

More: Natural Disasters Create New Challenges for Meetings Industry

Now, is every hotel going to say, “We’re going to waive all attrition?” No. They may say, “We’ll cut your attrition in half.” They may say, “We’re going to cut some other kind of deal with you.” As events move forward and venues are re-opening, they are going to be willing to try and work with you because they would rather have an event than have no event. Something is always better than nothing.

What is your opinion on whether “frustration of purpose” is necessary in a contract, and how specific does that needs to be?

These are complicated legal theories, so don’t rely on this as the end all, be all. But frustration of purpose means you could still have your event, but your reason for doing so is ruined.

If you’re contracting to have an event with JT Long as your speaker and JT Long is in the hospital, the hotel is still open, the people can still go there, but there’s no point, because JT Long can’t be there.

The purpose of having the event is then frustrated, and the law would let you out if the parties knew at the time of contracting that that was the purpose of the event. From a meeting planner perspective, the way you can take advantage of frustration of purpose is to make sure that your purpose is part of the contract.